Trajectories of Fragmentation II

Polycrisis, Intellectual Labor, and Transdisciplinary Research

There has been a longstanding awareness of the practical and theoretical insufficiencies arising from disciplinary fragmentation, one often book-ended by calls for the reorganization of academic and technical research and the development of a ‘meta-disciplinary’ discourse or methodological orientation. Across the 20th century, this has been reflected historically in three terminological waves: the rise of ‘interdisciplinarity’ in the interwar period, ‘multidisciplinarity’ in a postwar context, and the rise of ‘transdiciplinarity’ after the 60s. Although colloquially used rather interchangeably, they operate in unique conceptual registers. Interdisciplinarity, analyzes, synthesizes and harmonizes links between disciplines into a coordinated and coherent whole; multidisciplinarity, draws on knowledge from different disciplines but stays within the boundaries of those fields; transdisciplinarity meanwhile, integrates the natural, social and health sciences in a humanities context, and in doing so transcends each of their traditional boundaries.1

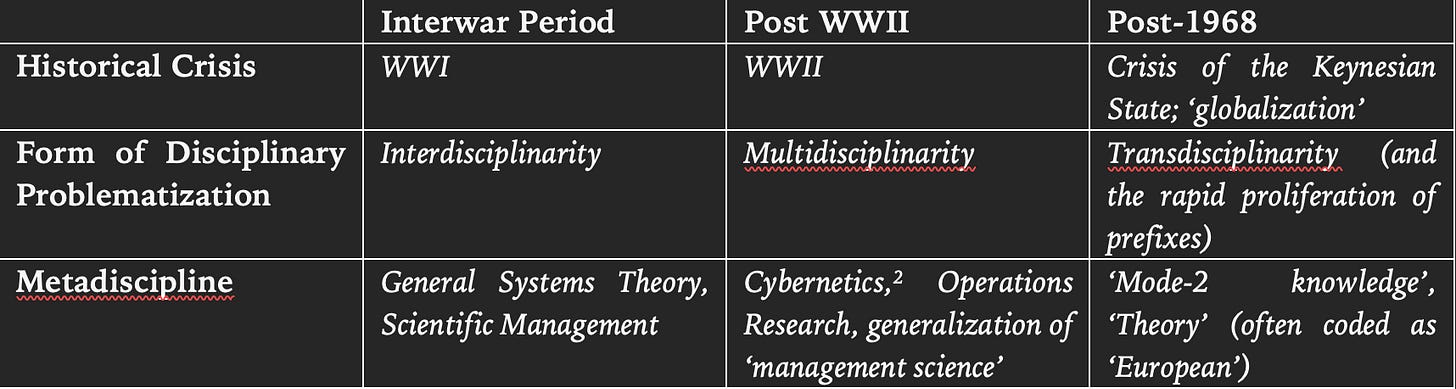

These waves overlap and do not represent a teleological development as much as they chart the problematization of disciplinary knowledge following the fragmentation of intellectual labor in general, one which across the 20th century has loosely followed cycles of historical crisis —> disciplinary problematization —> metadiscipline:

As noted by philologist Roberta Frank in her history of interdisciplinarity, as early as 1916 the President of the National Research Council emphasized the importance of fostering "subjects lying between the old-established divisions of science," insisting already in 1914 on "the inter-relationship of the sciences."2 The 1920s in particular saw the introduction of new terms for reciprocal interaction within a total system—one not always already divided up between disciplinary areas traditionally. Von Bertalanffy’s ‘General System Theory’ for example attempts to propose a solution to the problem identified in the book’s first sentence: “modern science is characterized by its ever-increasing specialization, necessitated by the enormous amount of data, the complexity of techniques and of theoretical structures within every field.”3 Indeed, the 20th century saw the production of various ‘systems-theoretical’ perspectives.

The Unity of Science movement campaigned in search of “grand and simplifying concepts”, Norbert Wiener, Gregory Bateson and others developed ‘Cybernetics’, and Jay Forrester developed ‘systems dynamics’—all were attempts to construct a discourse that managed to avoid what each saw as the siloed conditions of knowledge-production. Already by 1928, English political theorist and economist Harold Laski laments an academic parade of “endless committees to co-ordinate or correlate or integrate.”4

‘Multi-disciplinary’ in a postwar context became arguably the more fashionable term to describe this problematization of disciplinary boundaries, or at least the recognition of the necessity of related disciplines to work together in one fashion or another. This took on significant strategic and practical importance during the Cold War, with the institutional instantiation of this growing inter- and multi-disciplinary emphasis appearing paradigmatically in the form of the RAND corporation.5

It was in the wake of the crisis of the late 1960s and early 1970s however that this inter- and multi- disciplinary emphasis reached a kind of fever pitch, birthing the now ever-present multiplication of qualifying prefixes: (inter-, multi-, trans-, de-, anti-, in-, meta- and post-, etc.).6 The term transdisciplinary meanwhile first appears in 1970 at an OECD meeting in Nice.7 Its use only becomes widespread by the 1980s and 1990s. A growing concern with climate change served as a focal point in coalescing a movement for research across (trans) rather than simply between (inter) disciplines and policy focus areas.8

The recent historical-philosophical, environmental, and political discussions around the ‘anthropocene’ for example is testament to its conceptual functioning across different disciplines. By1985 ACLS Report to the Congress of the United States on the State of the Humanities all twenty-eight constituent societies acknowledge a desire to, “transcend disciplinary perimeters, melt boundaries, fill gaps, and escape narrow confines.”9 UNESCO even declared itself ‘a transdisciplinary organization,’10 sponsoring large international research events such as the First World Congress in Transdisciplinarity in 1994.11

In his history of the term, Osborne traces three related but separate trends within the history of transdiciplinarity. First, a ‘systems-theoretical’ perspective with a tendency towards, “a meta-disciplinary form of supra-disciplinarity, embodied in the idea of a common system of axioms for a set of disciplines.”12 Examples here include various forms of Systems Theory, which emphasize the production of methodological perspectives amenable to the sort of integrative education or innovation system not bound by disciplinary divisions.13 Second, a more direct and practically-oriented sociological literature related to science policy, with its focus on “large-scale social problems – mainly generated by environmental factors associated with globalization – but viewed as amenable to scientific solutions.”14 Finally, there is a literature focusing on research related to policy-solutions related to environmental sustainability and health in particular, one grounded in, “a framing emphasis on the non-disciplinary and problem based character of science.”15

All three share an understanding of knowledge as being resolutely practical and problem-based, of the sort arguably typified by Michael Gibbons’ concept of ‘mode-2’ knowledge production.16 Whereas “Mode 1” knowledge is concerned with research aimed at knowledge for its own sake (rather than for the sake of application; similar to the concept of ‘basic research’), “Mode 2” is knowledge aimed to solving practical problems that require the integration of different discrete skills and knowledge.17 As a kind of conceptual forerunner of the literature around ‘the polycrisis,’ the concept of a ‘public policy problem’ from an epistemological standpoint has been understood to be inherently ‘wicked’ since at least the early 1970s.18 For Wittel,

the classical paradigm of science and engineering—the paradigm that has underlain modern professionalism--is not applicable to the problems of open societal systems. One reason the publics have been attacking the social professions, we believe, is that the cognitive and occupational styles of the professions—mimicking the cognitive style of science and the occupational style of engineering—have just not worked on a wide array of social problems. The lay customers are complaining because planners and other professionals have not succeeded in solving the problems they claimed they could solve… The kinds of problems that planners deal with—societal problems—are inherently different from the problems that scientists and perhaps some classes of engineers deal with. Planning problems are inherently wicked.19

Policy problems and transdisciplinarity share epistemological terrain insofar as they both exist across multiple domains and involve not just academic disciplines and the interplay among them, but also practitioners seeking solutions. All three practically oriented strands thus represent a dominant and positive concept of trandisciplinarity concerned with application, proposing policy-based solutions amenable by state policy and, and therefore presupposing, for Osborne at least, “a certain kind of social-democratic, ‘educational’ welfare state, of which it represents a technocratic variant.”20

the established discourse of transdisciplinarity is thus overwhelmingly positive and organizational; it is a discourse of the state, albeit often in practice of state-like entities on a supranational scale, which lacks the means of programmatic enforcement of the classical nation-state. It nonetheless presumes state agency…as the bearer of its practical rationality.21

There is indeed a disjunction between the aims often implied by transdisciplinary discourse (both conceptually and politically), its assumption of a unified nation-state with means of enforcement at a global scale, and the actual uneven distribution of state capacity globally—a distribution often determined by factors outside the control of individual nation-states themselves.22 It is notable in this regard that recent popular terms like ‘polycrisis’ and ‘derisking’ are concepts with origins in transnational UN related institutions. ‘Polycrisis’ has its conceptual roots in the work of complexity theorist Edgar Morin who holds an academic chair at UNESCO,23 while ‘derisking’ makes its first appearance in a research program that was a collaborative effort between the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and Deutsche Bank.24

As Osborne points out as well, the dissemination of transdisciplinary discourse has therefore often been at the behest of sponsorship by international organizations. In its more aspirational moments, this disjunction lends the transdisciplinary style more than a bit of the glossy sloganeering common to international agency whitepapers and the non-profit sector; well-intentioned perhaps, but rarely connected to power or concrete forms of enforcement. Transdisciplinary discourse, much like the discourse around solutions to the polycrisis, seems to be a discourse in search of a political subject of action that does not yet concretely exist at a global scale.

While Osborne’s comments above are of course meant critically, its positivity and presumption of state agency is something I want to at least partially retain here, particularly given its relevance to recent debates over state capacity in a US domestic context. Mariana Mazzucato for example has appropriately called for the development of, “a new curriculum for global civil servants, one that eliminates the old-school notions from Public Choice Theory and New Public Management that continue to paint government as, at best, a market fixer, while also convincing many that government failure is more dangerous than market failure.”25

The dominant positive variant of transdiciplinarity is however undoubtedly the result of a focus on ‘holistic’ knowledge production across academic disciplines, orientated towards the production of solutions to ‘real world’ problems, however to the neglect of critical self-reflexiveness regarding questions of concept construction. In Osborne’s terms, it suffers from “an almost complete lack of fundamental theoretical work on the concept of a problem.”

Less common or at least less frequently associated with transdisciplinarity is the post-1960s wave of French and German ‘Theory’ and its influx into Anglo-American universities. Humanities and social science disciplines were in many ways almost wholly transformed following the reception of mid-century French and German thought, despite—or, perhaps, precisely because of—the fact that this transformation took place on theoretical bases that bore little relation to the particular histories of the disciplines which received them.26 The transdisciplinary dynamics internal to thinkers such as Foucault, Derrida, Guattari, and Latour for Osborne represent a more subterranean and negative (in the ‘critical’ sense) transdisciplinary tradition.27

These are of course some of the denaturalizing, anti-essentialising, and particularising forces that were understood as resolutely anti-empirical as well as corrosive in relation to existing disciplines, particularly in the social sciences and humanities (if not casting doubt on the ‘objectivity’ of the natural sciences). They also represent the kind of discourse those concerned with the practically-oriented forms of transdisciplinary are likely to refuse to engage in, despite the fact that they form a kind of negative side of a broader transdiciplinary trend of which they are a part.

The strictly practically oriented ignore this negative transdisciplinary trend at their own risk, because much of this literature now, at the level of academia at least, often functions more like philosophy than disciplinary philosophy28 in “constituting the most general concepts, to which the most general social and historical problems – the pragmatic basis of the research agenda in social needs – correspond.”29 They might not think they are doing philosophy, but they are.

Choi, BCK., and AWP Pak. “Multidisciplinary, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 1. Definitions, objectives and evidence of effectiveness.” Clinical and Investigative Medicine 29: 351-364.

Roberta Frank, “Interdisciplinary: The First Half Century,” ed. E.G. Stanley, T.F Hoad, Words (Suffolk: D.S Brewer, 1988): 139-151.

It is notable that von Bertalanffy’s classic appears first in German in 1928, but is translated into English in 1965, during the flowering of interest in inter, multi, and then transdisciplinary study. Luwig von Bertalanffy, Kritische Theorie der Formbildung, (Berlin: Gebruder Borntrader, 1928). trans. General System Theory: Foundations, Development, (New York: George Braziller, 1968): 1.

Quoted in Frank, 141.

Daniel Bessner, “Organizing Complexity,” Journal of the History of Behavioral Science, 2015 Winter;51(1):31-53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25418794/

Osborne, “Problematizing Disciplinarity, Transdisciplinary Problematics, Theory, Culture, & Society, 32(5-6) (20150): 5.

Its initial use is traditionally dated to the first OECD International Conference on Interdisciplinary Research and Education in Nice in 1970, which featured a notable paper by Jean Piaget. Jean Piaget, “The epistemology of interdisciplinary relationships.” In Briggs A et al., editors. Interdisciplinarity, Problems of teaching and research in Universities, Paris: OECD; 1972. pp. 127–139.

Jay Bernstein, “Transdisciplinarity: A Review of Its Origins, Development, and Current Issues,” Journal of Research Practice, (2015): 8.

Frank, 142.

Kim, Transdisciplinary: ‘Stimulating Synergies, Integrating Knowledge’. Paris: UNESCO, quoted in Osborne, 10.

Osborne, 10.

Ibid

Osborne, 9.

Ibid

Osborne, 12.

Michael Gibbons, “Mode 1, Mode 2, and Innovation,” In: Carayannis, E.G. (eds) Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, (Springer: New York, 2013).

Gibbons et al, The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Research in Contemporary Societies, (London: SAGE, 2012). https://sk.sagepub.com/books/the-new-production-of-knowledge

Originally presented in Horst Rittel, Melvin Webber, “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning,” Policy Sciences 4 (1973): 155-169.

See also, C West Churchman, “Wicked Problems,” Management Science. 14 (4): B-141-B-146.

Osborne, 11.

Osborne, 13.

Johnathan K. Hanson and Rachel Sigman, “Leviathan’s Latent Dimensions: Measuring State Capacity for Comparative Political Research,” The Journal of Politics, 83: 4 (2001). To say nothing of specific colonial or post-colonial dynamics.

On the 'Polycrisis': Part I

I. ‘Polycrisis’ is a concept best popularized by Adam Tooze. According to a report from the Cascade Institute however it can be traced to French complexity theorist Edgar Morin—who currently holds the (…wait for it…) UNESCO Chair of Complex Thought. The report quotes Morin’s 1999 book,

“Derisking Renewable Energy Investment” UNDP, https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/Derisking%20Renewable%20Energy%20Investment%20-%20Key%20Concepts%20Note%20(Mar%202014Versi%20%20%20.pdf

Mariana Mazzucato, “Reimagining the state: Market shaper, not market fixture,” online at: https://hewlett.org/reimagining-the-state-market-shaper-not-market-fixer/.

Francois Cusset, French Theory: How Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze, & co. Transformed Intellectual Life in the United States, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008).

“The great books of European theory in the second half of the 20th century all exhibit hitherto unexamined transdisciplinary conceptual dynamics. Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949), Sartre’s Critique of Dialectical Reason (1960), Levi-Strauss’s The Savage Mind (1962), Foucault’s Words and Things (1966 – translated as The Order of Things), Derrida’s Of Grammatology (1967), Deleuze and Guattari’s two-volume Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1972, 1980), Habermas’s Theory of Communicative Action (1981) and Sloterdijk’s Critique of Cynical Reason (1983)…are books that cross disciplines with a confidence and facility that belie the complexity of the exchanges between the different knowledges out of which they are constructed, in widely differing and often unstated ways.” Osborne, 14.

Overdetermined as it is, at least in the Anglo-American world, by a specific strand of ‘analytic’ philosophy.

Osborne, 20.

FYI - You may know all this but I learned today from Le Monde that Morin is not only alive but on Twitter (!), writing opuscules about Ukraine, sporting a velvet suit with flashy cravat and recommending that we all drink more wine. Also that in addition to "polycrisis" he coined the word "yéyé" - it is as if the person who came up with "beatnik" were still around. I'm still curious if he knows about Tooze.

https://www.lemonde.fr/le-monde-passe-a-table/article/2023/06/25/edgar-morin-je-crois-a-la-necessite-des-exces-dans-l-ivresse-collective_6179188_6082232.html