The Revenge of Use Values: Part I

Supply Chains, Bitcoin, and Lubricators of Velocity - Reflections on Banaji's Commercial Capitalism

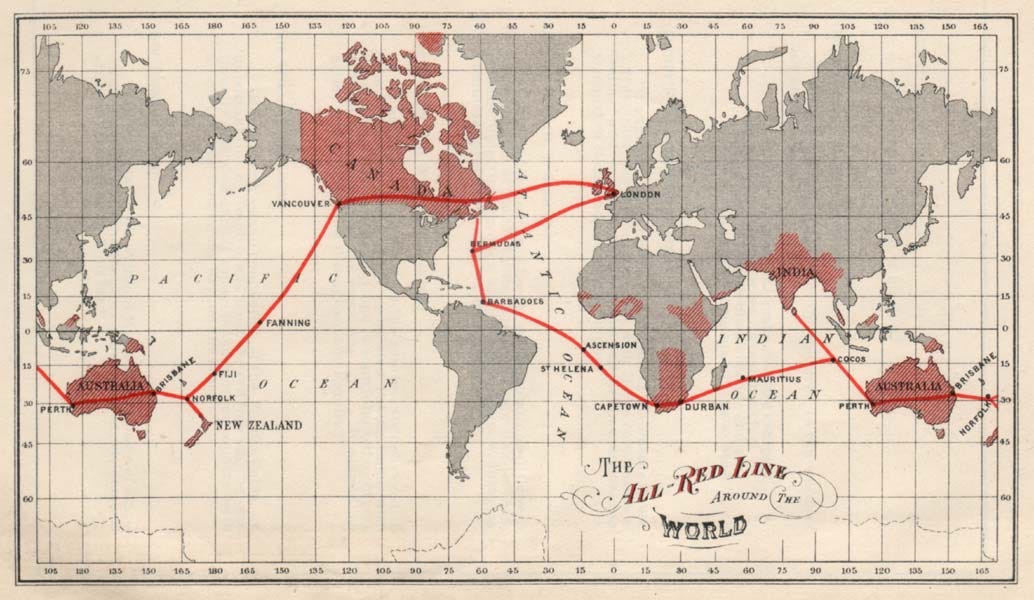

Thanks to the expansion of steam shipping, railways, and the introduction of communications technologies like the telegraph, the late 19th century saw incredible changes in the speed and spatial arrangement of capitalism. In a rather stunning note to Capital Vol III, Engels writes, “the colossal expansion of means of communication—ocean-going steamships, railways, electric telegraphs, the Suez canal—has genuinely established the world market for the first time.”1 If, as Tony Smith has argued, “the category ‘world market’ is implicit in each and every major theoretical level of Capital,”2 (if, in other words, Marx assumes a ‘world market’ as a condition of ‘capitalism’ presented as a theoretical model), than the world market properly speaking appears on the historical scene only after the publication of his analysis of capitalism—and yet a historical condition of capitalism is, precisely, a ‘world market.’ The unorthodox periodization that might follow places the beginning of capitalism not in the 15th and 16th centuries, but in the late 19th century.

Strange situation; however, lest this escape into a debate about periodization, the point here is to emphasize the way in which the physical conditions of exchange affect velocities of circulation; how the materiality of those systems mediating an entire global network of exchange relations establishes limits within which capital finds itself that it then attempts to supersede. These qualitative aspects help determine its ‘turnover time.’ Usually associated with the lifespan of fixed capital, the concept turnover time traditionally refers to the period of time where a piece of equipment can be in use; i.e., the total amount of time over which its value is transferred to products and returns to the capitalist as money. Engels though uses it in a much broader sense:

“the whole earth has been girded by telegraph cables. it was the Suez canal that really opened the Far East and Australia to the streamer”; “the turnover time of world trade as a whole has been reduced to the same extent (from months to weeks…) and the efficacy of the capital involved in it has been increased two or three times more.”3

In his 1977 classic The Visible Hand, Alfred Chandler famously explored this development via the history of railroads and the telegraph in the continental US 4 Originally a constellation of six firms, by 1866, Western Union had become the dominant telegraph company in the US, with yearly messages sent over its lines increasing from 5.8 million in 1867 to an astonishing 63.2 million in 1900. Over the same period, transmission rates fell from an average of $1.09 to 30 cents per message. Proving the importance of this communication infrastructure to the expansion of American capitalism, “Western Union was the first nationwide industrial monopoly, with over 90% of the market share and dominance in every state.”5 Regulation at a state and federal level was essentially futile.

The vast spread and consolidation of the telegraph network had a major impact on financial markets. The expansive telegraph network, “simply made possible the emergence of efficient, nationwide markets.” As JoAnne Yates puts it, “for the first time, market participants in distant parts of the country could interact almost instantaneously to gather information and make transactions.”6 The ability to coordinate pricing in New York led to the disappearance of hundreds of exchanges that had arisen across the country over the course of the 19th century.

In his A Brief History of Commercial Capitalism, Jairus Banaji points out how Marx was, “perfectly aware of these ‘material’ influences, of the way use-value as such could acquire economic significance.”7 While capitalist accumulation certainly runs up against obstacles imposed on it by the natural environment (which, in turn, it then attempts to supersede), the emphasis here is much broader and, in a sense, rather banal—the materials that make up transportation and communications technology function to mediate the speed and scale of accumulation, and therefore there is a vast ‘use-value’ stratum playing a determining role at the level of economic form.8 Probably the most famous expression of this can be found in the Grundrisse:

“The more production comes to rest on exchange value, hence on exchange, the more important do the physical conditions of exchange—the means of communication and transport—become for the costs of circulation. Capital by its nature drives beyond every spatial barrier. Thus the creation of the physical conditions of exchange—of the means of communication and transport—the annihilation of space by time—becomes an extraordinary necessity for it.”9

Capital by its nature drives beyond every spatial barrier—and through this process of destruction produces the ‘physical conditions of exchange’ (indeed, is there a more capitalist dynamic than construction via destruction?). In driving beyond every physical qualitative barrier in general the fantasy it poses for itself is the escape from qualitative mediation at all. This process of destruction produces a new spatial and temporal arrangement.

It is of course important to note that to view a commodity from the standpoint of its use-value is here not some sort of normative stance. It is not meant to be a judgment about its proper or 'most productive' use. It just means to view it from the standpoint of its qualities—its specific physical characteristics. Thus when Marx introduces the concept he writes, “the usefulness of a thing makes it a use-value, but this usefulness does not dangle in mid-air. It is conditioned by the physical properties of the commodity, and has no existence apart from the latter.”10

‘Usefulness’ here should therefore not be confused with a rendering of particular subjective preferences in the present; i.e., the concept of utility. The physical and material emphasis of the concept ‘use-value’ here stands for something temporally broader, including physical characteristics that are currently present in the object, but also those that might come to have social meaning in the future. In the case of magnetism, “[its] property of attracting iron only became useful once it had led to the discovery of magnetic polarity.”11 Certain materials, in other words, may become useful in new ways in the wake of technological discovery, but these new uses remain based on physical characteristics that have always been present in the object itself. Use-values make up the world of commodities' qualitative and material sub-stratum.

The economic doxa of the business press takes it for granted that technological innovation only becomes socially actual in a generalized fashion under certain conditions. Innovation does not in other words merely follow from ingenious invention. Clocks capable of measuring time in homogeneous units for example pre-date their widespread use. In his Politics of Time, Peter Osborne relates both the broad acceptance of ‘clock time’ and the rapid development of transport and communications technology to the imposition and generalization of a particular form of time under capitalist modernity:

“With capitalism came the homogenization of labour-time: the time of abstract labour (money, the universal equivalent), the time of the clock. And with the rapid development of transport and communications in the course of capitalist development in the nineteenth century (the railways and the telegraph) came the beginnings of a generalized social imposition of a single standard of time."12

There were certainly historical precursors to this generalized quantifiable continuum, such as Chinese water clocks dating to the 8th century13 or the equal blocks of time regulating life in Benedictine Monasteries.14 That time could be measured in homogenous units however did not alone allow or lead to the more efficient or effective arrangement of societies such that, all of the sudden, after its invention, everyone was able to be ‘on time;’ rather, the form of time measured by clocks became both widespread and naturalized when a particular social and economic compulsion to measure time in equal units became sufficiently generalized and, indeed, imposed upon forms of temporality that had been previously socially-determined in different ways (such as those determined by agricultural rhythms, religious rituals, etc).

It is of course tempting and even occasionally politically productive to emphasize the more romantic aspects of usefulness; to point out how the diversity of concrete aspects of an object is lost or forgotten when rendered equivalent by the logic of exchange; to argue for organizing economic production around the production of use-values rather than production of commodities for profit. A recent example is Cedric Durand’s association of the Left in general with what he calls the “revenge of use-values;” with the idea of democratically organizing production not for profit for the satisfaction of human needs.

“Unlike those monopolistic intellectuals favoring a regressive ‘techno-feudal mode of production’, or those in the investment community expecting economic dirigisme to engineer a rebound of accumulation, the left wants something else: after decades of commodity delirium, a turn to democratic planning—channelling investment according to social need and ecological boundaries—would be the revenge of use value.”15

This is all well and good, however the 'revenge of use-values' I want to emphasize is of a different kind. It is one which, in another guise, has been at the forefront of economic commentary and commented upon now almost ad nauseum: the economic effects (both real and imagined) of supply-chain disruption during the COVID pandemic. I emphasize both real and imagined because the perception alone of supply chain issues will effect investment decisions. As Claus Offe has put it in another context, “the power position of private investors includes the power to define reality…whatever they consider an intolerable burden in fact is an intolerable burden which will in fact lead to a declining propensity to invest…the debate about whether or not the welfare-state is ‘really’ squeezing profits is thus purely academic because investors are in a position to create reality — and the effects — of a ‘profit squeeze.’”16

In the Marxian jargon, this return of supply chains to economic consciousness is an instance of the use-value ‘form determination’ of value creation; a kind of return of the repressed of those qualitative physical limits that always shape and limit the form of accumulation and value-augmentation in historically specific ways.

The nature of our current historically specific arrangement undoubtedly comes out of a broader response by capital to the economic crisis of the early 1970s, and increases in speed and turnover are certainly one way to solve a crisis of profitability. Insofar as capital is itself not a physical object but a movement17 and increases in the speed of this movement lead to increases, intensifications, and more concentrated periods of circulation (a drive to more rapidly move through cycles of M – C – M’) is just as central to ‘capitalist growth’.18 Following the movement of capital and production processes in search of cheaper labour necessitated more fluid connectivity and the management of supply-chains across far-flung territories. In his Planetary Mine, Martin Arboleada argues this logistics revolution of the latter half of the 20th century, “has deliberately and decisively blurred the boundaries between making and moving – production and distribution.”19

Economic elites themselves have more recently adopted an increasing focus on speed and interconnection.20 According to the World Economic Forum, “there are three reasons why today’s transformations represent not merely a prolongation of the Third Industrial Revolution but rather the arrival of a Fourth and distinct one: velocity, scope, and systems impact. The speed of current breakthroughs has no historical precedent.”21 While descriptions of 'economic growth' are usually associated rhetorically with expansion, there is here an added emphasis on intensification and interconnection. This is neither a departure nor pablum, but perfectly consistent with the growth imperative of capitalist accumulation. In a rather literal sense, ‘growth’ occurs not simply by creating more goods to sell to new markets, but by intensifying or speeding up the existing circuits of both commodity and monetary circulation.

Beyond communications and transportation technology there is, to use Banaji's phrase, one other major “lubricator of velocity," one which very recently has come to the fore of economic consciousness in a similar way: the banking system.22 "The link was clearly seen by Marx," Banaji writes, "when he implied that the development of the credit system helped sustain a more rapid turnover of commercial capital." The discounting of bills of exchange certainly played a major role in financing both larger volumes of trade and a greater fluidity of circulation.23 For Banaji, "the new commercial methods that came into vogue during the 1860s revolved essentially around a more rapid velocity of circulation."24 The destructive effect that this had on existing networks of international merchants should not be underestimated.

Destruction through disintermediation is the central theme here. To illustrate this kind of destruction, Banaji references the autobiography of a Greek merchant named Dimitros Velekas. It is worth quoting in full:

“the most important reason [for] the disappearance of those merchant houses was the change that occurred in trading itself. Half a century before[,] the electric telegraph and the telephone [had not brought] the most distant countries in direct communication through instant understanding. The goods were loaded on sail vessels and months went by until they arrived [at] the port of consumption. In the meantime, the owners of the cargoes had enough time to speculate, by observing the fluctuation of the market. At that time the merchants depended on their own capital and on the credits of their correspondents; therefore, their transactions were very limited, but the dangers were also fewer than today, and moreover the merchants were more conservative. Today the growth of global trade has brought an increase of the number of banks; the banks concentrate maximum capital, which has to be invested (wherever it can be) . . . That way the turnover of dealings increased immensely…today one could say that commerce aims mainly to the gain of a small profit from big and rapid enterprises, which are continually repeated. The few merchants who succeeded in applying the new system are still trading in a profitable way. The old Greek trade does not exist anymore and those old merchant houses, where new generations of merchants found work in succession, are now dissolving, causing national damage.”25

In the sequel entry I’ll argue that while the return of the spectre of supply chains represents the revenge of use-value ‘form determinations’ on everyday economic consciousness (one which represses the very real and physical ‘use-value’ mediation of the process of value creation), the popularity of bitcoin is an ideological expression of this same fantasy of disintermediation, but at the level of the banking system; at the level of monetary circulation rather than commodity circulation. What may seem like two disconnected concerns are in fact deeply ideologically intertwined. The theoretical articulation of this force of disintermediation is probably represented paradigmatically in the thought of Nick Land, who connects the practical possibilities of bitcoin to previous theorizations of ‘accelerationism.’

Engels in Marx, Capital Vol III, 620 note 8. Quoted in Jairus Banaji, Commercial Capitalism, (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020): 115.

Tony Smith, “The Place of the World Market in Marx's Systematic Theory,” online at: https://www.academia.edu/12001003/The_Place_of_the_World_Market_in_Marxs_Systematic_Theory

Quoted in Jairus Banaji, A Brief History of Commercial Capitalism, 115.

Alfred Chandler Jr., The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1977).

Entry for ‘History of the Telegraph’ published by the Economic History Association. Online at https://eh.net/encyclopedia/history-of-the-u-s-telegraph-industry/

JoAnne Yates, “The Telegraph’s Effect on Nineteenth Century Markets and Firms,” Business and Economic History, Vol 16 (1986). Papers presented at the thirty- second annual meeting of the Business History Conference (1986), pp. 149-163.

Engels in Marx, Capital, Vol III. Quoted in Jairus Banaji, A Brief History of Commercial Capitalism, 116.

The supply-chain impacts that followed the COVID pandemic was, in this sense, a straightforward crisis of turnover time. It functioned as the mass re-extension of chains of circulation that had previously been shortened.

Marx, Grundrisse, 524.

Marx, Capital Vol I, 124.

Marx, Capital Vol I, 125 note 3.

Peter Osborne, Politics of Time, (London: Verso, 1995): 34.

https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/evolution-timekeeping-water-clocks-china-and-mechanical-clocks-europe

Eviatar Zerubavel, The Standardisation of Time: A Sociohistorical Perspective', American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 88, no. I, 1982, pp. 1-23. Quoted in Peter Osborne, Politics of Time.

Cedric Durand, “The End of Financial Hegemoney,” New Left Review 138, 2022. https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii138/articles/cedric-durand-the-end-of-financial-hegemony

Claus Offe, Contradictions of the Welfare State, (New York: Routledge, 2019): 151.

“Capital, as self-valorizing value, does not compromise class relations, a definite social character that depends on the existence of labour as wage-labour. It is a movement, a circulatory process through different stages, which itself in turn includes three different forms of the circulation process. Hence it can only be grasped as a movement. Those who consider the autonomization of value as a mere abstraction forget that the movement of industrial capital is this abstraction in action.” Karl Marx, Vol II, 185

“The second moment is the space of time running from the completed transformation of capital into the product until when it becomes transformed into money. The frequency with which capital can repeat the production process, self-realization, in a given amount of time, evidently depends on the speed with which this space of time is run through, or its duration…the velocity of turnover therefore—the remaining conditions of production being held constant—substitutes for the volume of capital.” Marx, Grundrisse, 519.

Martin Arbeleda, Planetary Mine, (London: Verso, 2020): 115. Quoted in Eugene Brennan, “Mapping Logistical Capitalism,” Theory, Culture, & Society, (2021): 1-12. This insight is arguably already present in Marx himself. “Economically considered, the spatial condition, the bringing of the product to market, belongs to the production process itself. The movement through which it gets there belongs still with the cost of making it…this locational moment — the bringing of the product to market, which is a necessary condition of its circulation, except when the point of production is itself a market—could more precisely be regarded as the transformation of the product into a commodity. Only on the market is it a commodity.” Marx, Grundrisse, 533-534.

Perhaps Klaus Schwab has been spending his summers in Gstaad reading Paul Virilo.

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/01/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-what-it-means-and-how-to-respond/#:~:text=There%20are%20three%20reasons%20why,breakthroughs%20has%20no%20historical%20precedent.

Marx, Capital, Vol III. Quoted in Banaji, 116.

Jairus Banaji, Commercial Capitalism, 77.

Ibid.

Quoted in Banaji, Commercial Capitalism

Jairus Banaji is one of the best of all time.